48 Hours in South Luangwa (part 1)

- Guy Mavor

- Oct 26, 2018

- 11 min read

June 2017 and I am teaching in Blantyre, in magical Malawi (see separate posts), for the term. A Friday off for Eid-al-Fitr, and Monday off for something else, mean that I have just enough time to pop to Zambia and back. I reckon. A stupid plan, but when am I next going to be this close - a mere day's drive - to the Luangwa Valley? And, after a couple of money-saving mishaps (one rental car double-booked, another with a wheel falling off as I drive it) I now have a beast of a car: a 4.2l v8 petrol go-anywhere land cruiser, borrowed from a friend, Moses. I have cash, camping gear, water and a bad map. And company, even, at least as far as Lilongwe. My cleaning lady Linly is taking her daughter Miracle to meet a friend for the first time. We are all excited.

Roads in Malawi are good when they are empty and trying when they aren't, as there are no dual carriageways and truckers are an impatient bunch. But as we drive past Lunzu, where Linly is building a house and planning her transition from working for others to working for herself, as a smallholder and landlady, the onrushing trucks on the outskirts of Blantyre give way to empty tarmac, with the low, rolling hills of the Shire valley around us. Eventually, we turn left towards distant mountains, climbing as we approach Ntcheu.

"I grew up here," Linly tells me. "At night the hyenas used to come down into the village."

"It doesn't look wild enough anymore," I reply.

"Yes, it is better now."

I reflect that living with dangerous wild animals is likely not as much fun, as easy, as dipping in and visiting them. Nevertheless, I am heading to an area where people continue to do just that. In Malawi, charcoal sellers line the roads near the remaining mountainside forest reserves and, over the last decade, the last free-roaming, crop-raiding herds of elephants have been moved into fenced parks. This decline, if it is in fact that rather than progress, is lamented by some Blantyre expats, but it is also true that the country's national parks are thriving as they have not done for decades, thanks to the intervention and management of African Parks (more on this elsewhere), a sudden sense of scarcity pushing a final conservation effort from both local and international NGOs and private tourism operators. It is working - visitor numbers are up, and there is a - tourist - buzz about Malawi.

It is also apparent from driving along the border highway with Mozambique towards Dedza, and from crossing into Zambia the next morning, that the country has a much higher population density than its neighbours, with a high, rolling plain and very little settlement to my left, in Mozambique, and a village at least every half-mile to my right. It isn't just that there is more water on the mountainous Malawi side, it is a density I have encountered everywhere in the country, even on the dry, scrubby, baobab-studded plains south of the lake.

At Dedza we stop for at late lunch at the famous pottery. Their apple strudel is fantastic, as is the pottery, but it is late. We move on to Lilongwe, stopping only for a speeding ticket (oops), and arrive at dusk in a city in virtual gridlock. After an hour of crawling, we get to the reason: Friday prayers at the city's central mosque, its size magnified further by floodlights in a city in the midst of a power cut. I watch smiling crowds stream out, no longer frustrated at the delay - I have a day off for this after all. And, after dropping Linly and Miracle off, I am suddenly through the 'city' - not for nothing is it known as the Capital Village - and at my campsite in time for chambo, fried lake fish, chips and a beer.

I am at the border just after dawn, and it is smoother than you would think. There are 5 stages: getting yourself out and into Zambia, getting the vehicle out and in, and getting temporary insurance and road fund licence in Zambia. For the last two, a lady presented herself to me to guide me through the steps, or at least from office to office. I assume she was on commission as I did not pay her. Also at the border is a cashpoint dispensing Zambian Kwacha, as well as several dozen 'freelance' money changers offering a better rate. To their dismay, I choose prudence, and the electronic route. Otherwise, as long as you have the right pieces of paper from you rental company or the owner, you can get through in under an hour.

And then I reach Chipata: smarter and more prosperous than anywhere back across the border. I stop for a stupidly posh breakfast at an incongruously grand hotel, then turn right for the Luangwa, across increasingly open, sparsely populated countryside. The first glimpse of the valley whets the appetite, a drop down a shallow escarpment into a seemingly endless expanse of bush. But that is not the whole story. The valley's population is growing rapidly, and part of my trip is to see the non-wildlife businesses away from the river and park, on the populated western side, which also drive the local economy.

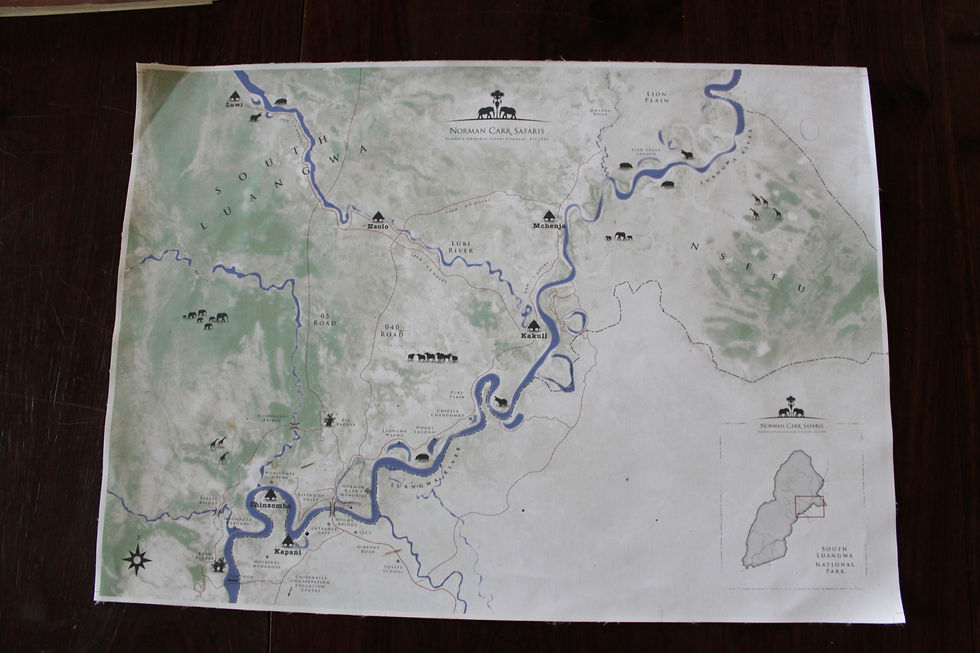

But my first stop is a kind of pilgrimage for this website: a trip to Norman Carr Safaris, at its former camp, Kapani, now the headquarters of Time and Tide/Norman Carr, on a seasonal oxbow lagoon. The company now is a 21st-century incarnation of an earlier model. Glossier sales pitches, high prices, a stupidly luxurious main camp, Chinzombo (it is amazing, I'll grant you). But its bushcamps have a clearer lineage to the man himself, the pioneer in the country, and indeed in the south of the continent, of an intense version of eco-tourism - walking in the wild, among wild animals, with people who know them intimately. The Luangwa's small bush camps (run by Norman Carr Safaris, the Bushcamp Company and Robin Pope Safaris, among other small-scale specialists, wedded to the landscape) are simple but beautiful, comfortable, and the cooking is often miraculous given the setting. The larger camps along the river are a little bigger but also low-key, and cater for every budget. I would even say, at the lower end, it is one of the best-value, properly wild safari areas in Africa (at least once you get here). Both at the top end, where it is - possibly - unnecessarily luxurious, and in the middle, at camps like Flatdogs, it is simply glorious. And it is worth noting that, as a rule in the valley, the more you spend, the more you are putting into the community. There are no extraction operations here.

A former colonial elephant controller (read: shooter of crop-raiding beasts), Carr was only too aware that development and abundant game did not go well together, and saw clearly that free-roaming abundance was coming to an end elsewhere. He encouraged Senior Chief Nsefu - Paramount Chief of the Kunda people in the Luangwa Valley - to set aside a portion of tribal land as a Game Reserve and built the first game viewing camp open to the public in the whole country. This visionary joint action was taken to secure both the wilderness and local people's future, and is a model broadly followed by other areas and countries. Botswana's tourism sector is largely founded on the principle of development through conservation, as is this website. And it lives on in the valley, with support from all lodges for local development projects under the umbrella of Project Luangwa. They could do more, I'm sure, but they do more than most other areas I have visited.

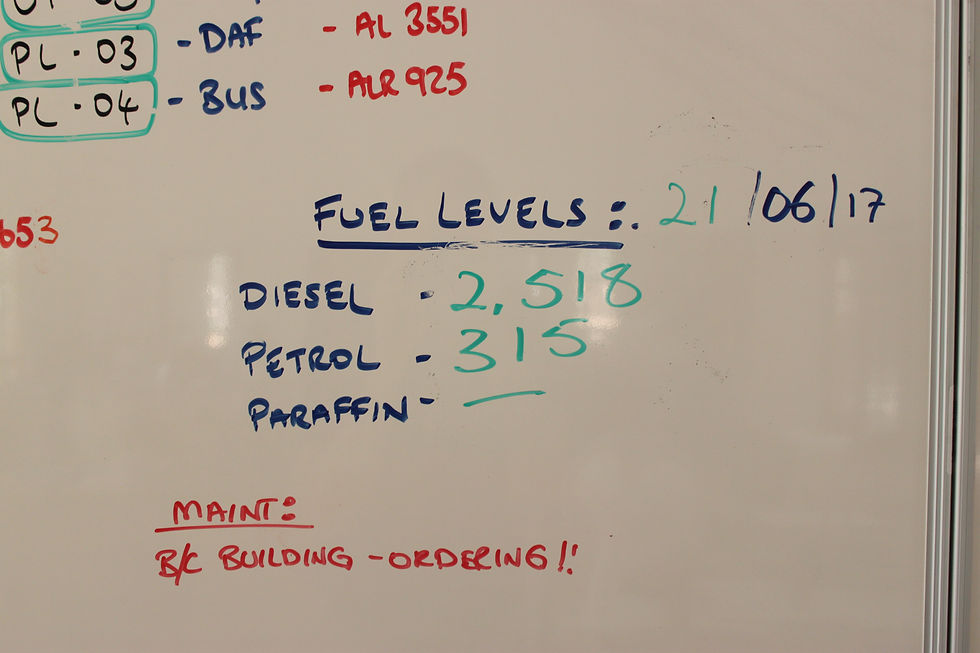

I sit chatting to Dave Wilson, who runs Norman Carr and is passionate about his operation. He is keen to give me numbers, both cardinal and ordinal ($300,000pa to community initiatives, 167 employees, training, clear career pathways; the first local guides, female guides, support for local disabled kids, and many more). Afterwards, I look around his place of work. A huge communication mast, a large fenced vegetable garden, generators, guest rooms now converted to houses. Self-sufficiency is the key, although the catering supply chain is less local than in comparable operations in Malawi, possibly because of population densities - there are simply fewer growers nearby. In the office are dozens of boards with land and air arrivals and departures, fuel levels, maintenance schedules, guide rotas, guest transport plans to remote camps.

I recall a presentation a couple of weeks earlier from Alistair Tough, on Norman Carr's early life, at the Blantyre Historical Society. He opens with a photo of Norman sat drinking tea at a table in a mud-and-reed-walled hut, open to the bush, with a lion lounging at his feet, and a question is asked to get us all going: "In this photo, what is the key to understanding Norman?" We respond with suggestions - the lion, the ammunition box, a good cup of tea? None of us spot the open briefcase behind him, full of files - his accounts and logistical plans. The business side is more obvious here at Kapani, but the bush is still just outside, and a joy to Dave and his family, and everyone who works here, every day. I walk down to the lagoon, no longer flooded but still green. Puku graze, and I spot a family of banded mongooses. Dave lives here with his wife Kate, who runs the extraordinary Mulberry Mongoose jewellery store along the road, and their two young girls. Predators regularly pass through, across the lawns, as do elephants. What a life! A quick stop at the lodge's old reading room to see Norman's picture, imagine him out in camp nearby, and I am off.

I move on to Mulberry Mongoose, stopping on the way to watch a family of elephants drinking from a pool next to a pod of hippos. Its carefully-crafted output is original, to say the least: guinea-fowl feather earrings, snare-wire bracelets. I would call it 'killer fashion', but thankfully it is repurposed before getting to that stage, thanks to the efforts of anti-poaching, de-snaring patrols. The shop - online too - exists to channel funds towards these conservation efforts, to employ and train local jewellers, and to diversify the local economy.

My next stop is the Wildlife Camp, spread out along nearly half a mile of riverfront. It is run by and for the Wildlife Society of Zambia, and, like my campsite for the night, Croc Valley, has a range of accommodation, with tents, chalets and camping spots, as well as a hide overlooking a water hole. It looks great, but I don't see anyone apart from overlanders camping in the distance. If this were in the Kruger, there would be dozens of bungalows for all budgets, and it would still be one of the nicest rest camps. As it is, it looks a good place to get away from it all. There are many more in this section of the valley. Before I get to Croc Valley I stop at Marula Lodge, with colourful fabrics and huge sausage trees, which runs great value trips into the park for backpackers, and Track and Trail river camp, which I find out later is on the site of an old crocodile farm once run by Croc Valley's current owner, Charl, back in the 80s. Both are lovely, friendly, well-run lower-budget options in prime sites, as is Thornicroft Lodge further along the river. Behind them all I stop and watch a small herd of giraffes watching me.

I have brought my tent, but for $10 more I can sleep in a bed in a simple tent at Croc Valley, so I do. As I unpack I watch banded mongooses pass by, then baboons as it gets dark. I move over to the main bar area, next to a large pool, which, I'm told, is a social hub for other local lodges. The lodge isn't busy, but is very welcoming. It is also right on the river, but also has chalets on stilts facing away from it, beyond the rugby pitch, overlooking a large seasonal pond, which is looking dusty by the time I visit (end of June). In the half day and night I am there, I miss wild dogs by a few hours, and a male lion stalks past the chalets. On this side of the river, we are not even in the National Park (so park fees are not payable, only a local conservation levy), making it staggeringly good 'value' wildlife. But, although I would urge anyone who thinks they can't afford a safari to think again and consider places like this, this is not really why I am here, and it is true to say that the more you pay at a lodge in the Luangwa, the better-paid, trained, and indeed senior, its local employees are, and the more they benefit the local economy. Flatdogs Camp nearby is a shining example of this. It once hosted campers too but has moved a little upmarket in recent years. I'll stay there tomorrow night, for $40 (the fee per person for a large safari tent with a bathroom - their luxury ones are more). Tonight, I am suddenly exhausted, and go swiftly to bed after dinner. A praying mantis welcomes me in, and I wake in the night to the sound of nearby hippos and smaller, scratchier creatures, but mostly I sleep. It's been a long two days.

I am up before dawn on Sunday, ready to drive the beast over the bridge into the park. I join the queue...of five vehicles (but peak season is another two weeks off, so there could be five times the traffic, which might make anyone who has tried to get around a Kenyan national park in July and August smile - and book a flight to Zambia). Beneath me, a fisherman in a mokoro poles himself out into the river in the dawn light. I soon see elephants, zebra, puku, and drive past a large pool full of hippo next to the large, luxurious Mfuwe lodge, the Bushcamp company's main hub, which is more a spectacular small luxury hotel than a bushcamp. I will return later, to walk through the famous elephant-frequented reception, although the wild mango trees they are seeking out on its lawns are not yet fruiting, so I will not see them. It is not birding season, but I see a fish eagle, crested cranes, lilac-breasted rollers and gangs of guinea fowl roaming the lanes. The noise of the bush waking up is spectacular. I spend 20 minutes with an old male giraffe, hanging out on the road. I am not sure what he is doing - warming up, perhaps? Posing, certainly. He is magnificent, with the knobbliest knees I have ever seen. A big loop inland takes me past more herds, before I turn back to the river and find a quiet spot to sit up through the sunroof, watch hippos and eat a breakfast of biscuits. Three male elephants approach from the other bank and wade out to drink. A fish eagle sits on a tangle of flood-marooned tree stumps in mid-stream. It takes me a while to register that I have only seen one other vehicle since crossing the river two hour before. I am in my own private Eden. I drive on, stopping to watch a small herd of elephants grazing by the road. They are eating the long grass, but first they must shake the dust off, and the sand off the roots. I watch them uproot large clumps, bash them repeatedly on a tree trunk, then gorge.

I move on to Mfuwe Lodge, set between a hippo and algae-filled pool and a fast-drying oxbow lake, where I meet Ian Salisbury, the general manager, who first came to the Luangwa Valley in the 70s and moved permanently in 1983. He gives a friendly, low-key tour (because, frankly, the lodge sells itself - lovely open areas and deck, a bush spa, pool, lovely rooms, great food), and we chat over a coffee, watching ever-busy banded mongooses (them again) and puku from the deck. The Bushcamp Company is run from here, and has the only 6 camps within the southern section of the park, in remote and glorious locations with friendly and extremely knowledgeable, well-trained and indeed well-remunerated staff (i.e. in senior roles). Guests tend to stay here initially and head out to a bushcamp afterwards, but many choose to head straight out, while some prefer the comforts of this central base.

Really, 'staff' is too neutral a word for this valley as a whole. At Flatdogs (see part 2), and to a lesser extent even at Croc Valley where I drove myself in and out, I felt hosted, welcomed, guided, involved, by all 'staff', and I know from many quarters that this is how it is across so many camps in and around the park. Being in the Luangwa Valley really is a special, immersive experience, a connection with the place and people, achieved apparently by simply walking out into the wilds with your guide, but in fact by a massive collective effort. And at the risk of sounding like Schwarzenegger again (see also Limpopo blogs), I'll be back for more. (Read part 2 for Flatdogs and more on other businesses in the valley).

Comments